Revolvers

Collecting the First Colt Clone

By Dan Shideler

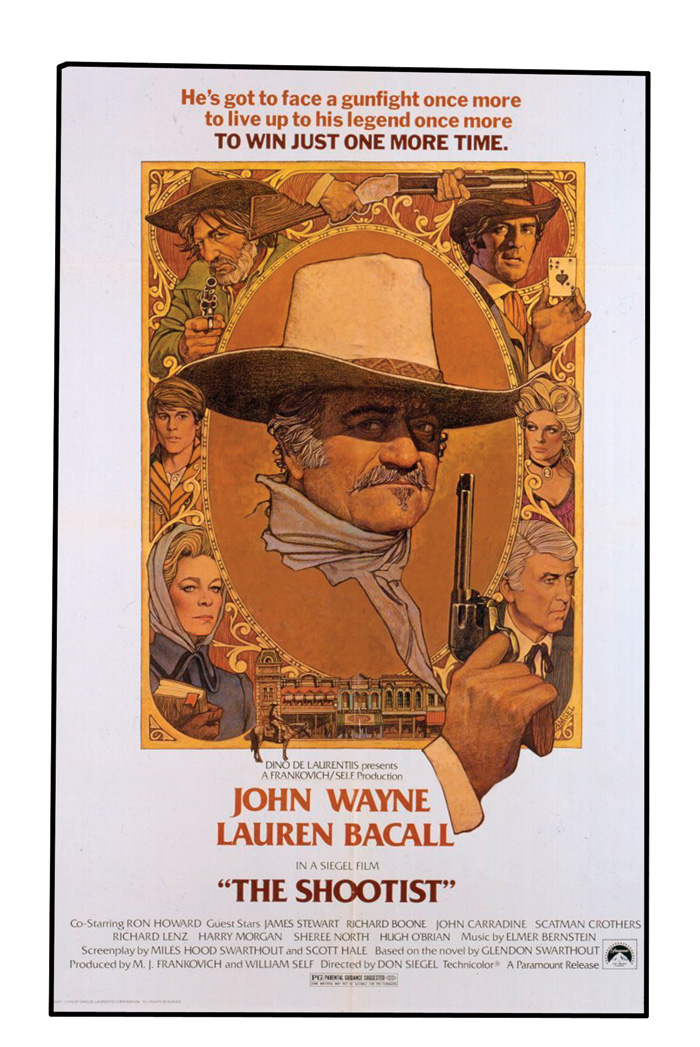

Heads up, trivia buffs. Here’s a poser: In John Wayne’s last movie, The Shootist, 1976, what make and model of six-gun did he use?

Are you kidding? Everybody knows The Duke used a first-generation Colt Single-Action Army. True, he usually did. But in his final movie, Big John used a Great Western Frontier Model in .45 Colt.

Odd as it might seem today, for a brief time in the mid-1950s, revolvers made by the Great Western Arms Co. of Los Angeles, Calif., were the beau ideal of the American handgun scene. At that time, Colt’s SAA was out of production, Ruger’s Vaquero wasn’t even a twinkle in Bill Ruger’s eye, and the Italian houses of Uberti and Pietta hadn’t been founded. If you wanted an authentic, brand-new single-action .45, you wanted a Great Western.

Decline of the SAA

Anybody who’s seen The Shootist, John Wayne’s final movie, is bound to be struck by the parallel between the on-screen plot involving a dying old gunfighter and the real-life spectacle of a terminally ill Wayne giving his last on-camera performance. But ill as he was, Wayne took care of his guns. As Doc O’Meara relates in Guns of the Gunfighters, the script of The Shootist called for Ron Howard, who had just killed Wayne’s assassin with Wayne’s revolver, to fling down the gun in disgust. Wayne then grinned approvingly and breathed his last. But Wayne, who used his own embellished Great Western revolvers throughout the film, wasn’t about to let Howard or anyone else fling his beloved guns around. What you saw Howard throwing to the barroom floor in that final scene wasn’t a Great Western but a carefully modified Ruger Blackhawk — a gun that helped put Great Western out of business. Talk about poetic justice. — Dan Shideler

Today, most people don’t know Great Western, the first Colt SAA clone, existed. No wonder, because even reference books can’t get it straight. One says Great Western’s guns were imported from Germany. Wrong. Another says they were imported from Italy. Wrong. Another says the company was headquartered in Venice, Calif. Wrong. To be fair, Great Western’s brief manufacturing life span — eight years — didn’t afford much opportunity for extended scholarship. But there’s a story there nonetheless.

As everyone knows, all modern solid-frame, single-action .45s have their roots in the classic Colt Model 1873 Single Action Army (that is, the Colt Model P). With its one-piece frame, hand-fitting grip, side-mounted ejector rod and characteristic “click-click-click-click,” the Colt SAA defined an era of American history. A list of shootists who favored the SAA or its civilian counterpart, the Peacemaker, reads like a who’s who of the wild West: Emmett Dalton, Wyatt Earp, Pat Garrett, John Wesley Hardin, Teddy Roosevelt, Doc Holliday, Belle Starr, Bat Masterson, Bill Tilghman, Tom Threepersons and Elmer Keith. (Doc O’Meara presents a wonderfully readable overview of the SAA and those who preferred it in his books Guns of the Gunfighters and Colt’s Single Action Army Revolver, published by Krause Publications.)

By the end of World War I, however, the single-action .45 was on its way out. The semiauto and double-action revolver were clearly the wave of the future, and they conspired not to praise the old SAA but to bury it. From a peak of 18,000 units in 1903, SAA production dwindled to just 800-plus units in 1940, its final year. At the time, the Colt SAA was the only full-sized, fixed-sight, single-action revolver made in the United States. A relic of bygone days, it was as anachronistic in mid-20th century America as the Pony Express. Immediately after WW II, Colt discontinued the old trooper with no thought of bringing it back.

The New Old West

In the late 1940s, however, a strange thing happened: America entered a twilight zone of old-West nostalgia. Ghost Riders in the Sky by Vaughn Monroe topped the jukebox charts in 1949. Popular radio dramas included Tales of the Texas Rangers and Frontier Town. Two of the top 10 television programs of 1950 were westerns: The Lone Ranger, starring Clayton Moore, and Hopalong Cassidy with William C. Boyd. The next year, Gary Cooper won an Oscar for his portrayal of Peacekeeper-toting Sheriff Will Kane in High Noon, and the movie’s folksy theme song, Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darling, went top 40.

Don’t ask me how it got started. Perhaps it was a subconscious longing for a simpler, preatomic age. Regardless, thousands of middle-aged suburban men who wouldn’t know which end of a horse the feedbag goes on suddenly started wearing bolo ties and rattlesnake boots and saying “howdy.” Dude ranches sprang up across the Southwest. Everybody, it seemed, wanted to be a cowboy — or at least pretend to be one.

That popular longing for the good old days of the wild West eventually made an impression on William B. Ruger. With his keen ability for identifying trends, Ruger realized he stood at the brink of a vast new market. Investing the proceeds of his popular .22 semiauto pistol into new design and tooling, in 1953 he introduced his Single Six .22 single-action. With its 19th-century styling, the Single Six was a smash hit and proved there was a market for the single-action revolver. But as nice as the gun was — and is — it had two shortcomings: It was “just a .22,” and it wasn’t a “real Colt.”

There apparently wouldn’t be a “real Colt” any time soon. At the time, Colt Firearms Co. was sitting fat and happy with a bushel of Korean War government contracts and saw no need to resume production of an 80-year-old design. Meanwhile, prices for used SAAs, Peacemakers and Bisleys — even doggy ones — shot through the roof.

But nature abhors a vacuum, and so did William R. Wilson, a California gun enthusiast with a strong entrepreneurial sense. There was a demand, and he would fill it. According to Bob Deubell — whose Web site, www.greatwesternfirearms.com, is a treasure trove of information — Wilson approached Colt in 1953 and asked if it planned to resurrect the SAA. Colt said the SAA was done.

But nature abhors a vacuum, and so did William R. Wilson, a California gun enthusiast with a strong entrepreneurial sense. There was a demand, and he would fill it. According to Bob Deubell — whose Web site, www.greatwesternfirearms.com, is a treasure trove of information — Wilson approached Colt in 1953 and asked if it planned to resurrect the SAA. Colt said the SAA was done.

Great Western Rises

A man on a mission, Wilson returned to Los Angeles, where he wasted no time enlisting partners and tooling up a factory on Miner Street, starting the Great Western Arms Co. Inc. to produce copies of the classic Colt SAA. Wilson was the new company’s president, and its first product was the Great Western Standard Model. Guns started rolling off the line in May 1954 and incorporated some genuine SAA components Wilson had procured from Colt.

Wilson subsequently enlisted Hy Hunter of Hollywood to handle marketing and distribution. A prominent gun retailer and firearms importer, Hunter merged the Great Western line into his existing retail and mail-order distribution channels, which were crammed with numerous Belgian, German and Italian guns. The persistent rumors that Great Western’s guns were manufactured abroad probably originated with the company’s association with Hunter. By about 1960, Hunter’s line included a West German SAA knockoff that looked pretty much like the Great Western, so perhaps you might be excused for assuming that the Great Western line was imported.

It wasn’t. All Great Western Arms Co. guns were manufactured in Los Angeles.

Except for some minor dimensional differences, the Great Western Standard Model, later called the Frontier Model, was the spirit and image of the Colt SAA in all major respects except one: its hammer. The Colt had a hammer-mounted firing pin, but the Great Western’s firing pin was mounted on the frame. The design originated with Idaho gunsmith Herb Bradley in the 1930s and was subsequently refined by Christy Gun Works of Sacramento, Calif. According to Deubell, the first several hundred Great Western Frontiers used a genuine Colt SAA hammer with integral firing pin. After 1955, a Colt-style hammer was available as an option for an additional $8.

Great Western Product Line

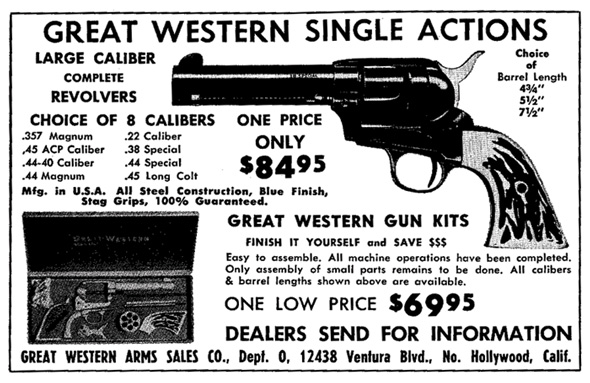

The flagship of the Great Western line, the Standard Model, was a fixed-sight SAA copy available in 43/4- , 51/2- and 71/2-inch barrels. Chamberings were advertised as .22 Long Rifle, .22 WMR, .38 Special, .44 Special, .357 Magnum, .38-40, .44-40, .44 Magnum, .45 ACP, .45 Colt, and “.357 Atomic.” The Atomic was a nonfactory .357 Magnum load incorporating standard brass, 16 grains of Hercules 2400 and a 158-grain bullet. Some claimed the .357 Atomic churned up 1,600 feet per second at the muzzle, which would have made it a real scorcher for its day. (For today, too.) Apparently, 50 or so Great Westerns were chambered for .22 Hornet, which was something unique: the first factory revolver to be chambered for a high-velocity varmint cartridge. According to Keith, some Standard Models were also chambered in .30 Carbine, another first, if true.

Some of those chamberings probably existed only in Great Western catalogs, as no production examples have been identified. As was true with many small gunmakers, there was apparently a reality gap between what Great Western’s catalog stated and what it built. No company production records remain, but Deubell, with whom Great Western is something of a passion, estimated that 50 percent of the company’s production was chambered for .22 rimfire.

A Buntline version with a 12- or 121/2-inch barrel was offered, as was a 31/2-inch-barreled Sheriff’s model that lacked an ejector rod assembly. A target version, the Deputy, featured a 4-inch barrel, a target front sight, an adjustable rear sight, and a full-length rib similar to the old King target rib popular in the ’30s and ’40s. A Fast Draw model with tuned action, brass grip frame and short front sight completed the revolver lineup.

Great Western also manufactured about 20,000 clones of the Remington Model III double derringer chambered in .38 S&W and .38 Special. The indefatigable Hunter simultaneously imported a West German double derringer that looked much like the Great Western, which further reinforced the impression that Great Western guns were shoddy postwar imports.

Actually, Great Western guns were built to take some punishment. The Standard or Frontier Model, for example, used the finest materials. The frame was forged steel. The hammer was made from 6150 chrome-vanadium steel. The hand, trigger and cylinder bolt were made of beryllium copper, and cylinders in calibers .357 and larger were made of 4140 chrome moly steel. That’s a lot of beef.

Actually, Great Western guns were built to take some punishment. The Standard or Frontier Model, for example, used the finest materials. The frame was forged steel. The hammer was made from 6150 chrome-vanadium steel. The hand, trigger and cylinder bolt were made of beryllium copper, and cylinders in calibers .357 and larger were made of 4140 chrome moly steel. That’s a lot of beef.

Finishes? Name it. You could have a Great Western in plain white metal; blued steel with case hardening; or Parkerizing, nickel plating, silver plating or gold plating, with or without engraving. If the faux-stag “Pointer Pup” grips didn’t thrill you, maybe ivory or mother-of-pearl would. For a buyer who wanted tosave $20, Great Westerns were available in kit form — in white — for all calibers except .44 Magnum. Henry M. Stebbins said in Pistols: A Modern Encyclopedia, published by Stackpole in 1961, that the kits weren’t aimed at average shlubs.

“(These kits) aren’t for amateurs,” he wrote. “The machine operations are done, and instructions come with the kit, but the deburring, fitting, polishing and finishing are for the buyer to do or to have done. This calls for gunsmithing skill.” Kit guns were marked with a “0” serial prefix.

Fans and Detractors

Great Western peaked during its first few years. In a masterpiece of marketing straight from the pages of Col. Sam Colt, Wilson presented President Dwight Eisenhower with a beautiful Great Western. Wayne was given a pair of engraved, gold-trimmed, ivory-stocked Frontier Models. (He carried those in The Shootist.) California Gov. Goodwin J. Knight was given an inscribed presentation revolver, a gun now in Deubell’s collection.

Dee Woolem, a stuntman at Knott’s Berry Farm in California, went to bat for Great Western after perfecting a quick-draw technique that earned him the title of “father of fast-draw.” Woolem traveled the country, promoting himself and his new gun. Those celebrity tie-ins provided a promising start for Great Western, but all was not well.

It is not recorded that Wilson had a detailed understanding of the labor-intensive nature of firearms production. His company obviously lacked Colt’s 120-plus years of handgun-building experience. There is no question that Great Western used the finest materials, but its regular production guns were too often characterized by abysmal fit and finish. Word about that soon spread, aided by Keith, America’s most prominent handgunner.

In one of the most damning firearms reviews ever printed, Keith hammered Great Western in his popular 1955 book Sixguns, published by Bonanza Books.

“The (Great Western) gun we tested was very poorly timed, fitted, and showed a total lack of inspection,” he wrote. “The hand was a trifle short, the bolt spring did not have enough bend to lock the bolt with any certainty, the main spring was twice as strong as necessary and the trigger pull about three times as heavy as needed. … As received, it certainly was neither safe, nor in shape to have been put on the market.

“There is no earthly reason why this new single action could not be just as good as the famous old Colt, but it will have to have a lot of redesign work to ever make it superior. … I cannot recommend them as finished arms.”

Keith’s blistering review constituted Strike One for Great Western.

Strike Two was Ruger’s introduction of its Blackhawk single-action in 1955. The magnificent revolver had an indisputable “cowboy” look despite its adjustable rear sight and tall ramp front sight. Unlike the old Colt and Great Western, it was a “modern” single-action that featured coil, not flat, springs and an investment-cast frame that shaved cost without sacrificing strength. And, wonder of wonders, the Ruger Blackhawk retailed for about $87.50, which was $4 less than the Great Western Frontier at $91.50.

Strike Three was Colt’s crushing 1956 announcement that, on second thought, it would bring back the SAA. Faced with a creeping tide of red ink because of the cancellation of its Korean War contracts, Colt reversed its earlier decision, called the old SAA in from the bench and marketed it energetically. The high-quality Colt was everything the Great Western was — and everything it wasn’t, too. The new second-generation Colt retailed at $125, or 37 percent higher than Great Western’s comparable model. Price, however, was no object: Colt’s renowned quality and the genuine romance of the magic Colt name easily trumped the contrived romance of the Great Western.

Ruger and Colt splashed their new sixguns throughout the firearms media, advertising in prestige publications such as American Rifleman, where their full-page ads appeared regularly. The inevitable effect was that Great Western got lost in the noise generated by Ruger and Colt.

Too Little, Too Late?

That was too bad. Most authorities agree that by about 1960, Great Western had a handle on its quality problems. Wilson had hired Dwayne Kastrup, a leading Colt SAA technician, as Great Western’s chief gunsmith. Kastrup’s influence was immediate and profound. In the second edition of Sixguns (1961), Keith sounded a conciliatory, admiring note.

“When we started this book, we could not recommend the Great Western Single Action,” he wrote. “Since then, we are happy to report Great Western has really gotten on the ball and is now cooking on all four burners. All the late manufacture Great Western single actions we have seen and tested are excellent arms: accurate, properly timed and adjusted and for the most part have good trigger pulls.”

Then came the stunner: “The Great Western Arms Company of California is now turning out better finished and fitted single actions than any we have seen from Colt,” Keith wrote.

It was quite a reversal of his earlier opinion. Stebbins was also sympathetic in his 1961 book.

“The Great Western Arms Company is ambitious and progressive,” he wrote. “It’s perfectly possible that they will build a single-action that’s of better quality than present or past Colts, as well as of more durable modern design. Some would even say, without qualification, that they now make the best.”

But the accolades were too little, perhaps, and certainly too late to help Great Western. Few firearms companies had fallen so far so quickly. By 1959, Great Western’s production of finished guns had become sporadic. Gun Digest stopped recognizing Great Western after its 1959 edition, and as far as I can tell, editor John Amber never gave it another thought.

In 1959, the assets of the moribund Great Western Arms Co. were purchased by gun importer E&M Co. (Early & Modern Firearms, now EMF). E&M attempted to carry on the Great Western name, promoting whatever finishedgoods remained in stock and heavily pushing the Great Western kits. A sales organization, Great Western Arms Sales Co., was established in North Hollywood, Calif. The company continued to promote Great Western products. However, by mid-1964, Great Western’s advertising was of a quality usually reserved for do-it-yourself earthworm farms.

Then, poof. Great Western winked out, going gentle into that good night.

What Remains

Because no production records remain, it’s difficult to construct a manufacturing chronology of Great Western’s final years. It seems likely that when E&M acquired Great Western, it marketed completed guns and then assembled what finished guns they could from parts. After that, kits and spare parts would have been all that remained. Such a scenario would explain the inconsistent nature of much of Great Western’s late production.

Today, EMF is a leading importer of single-action revolvers and other cowboy-action guns. Forty years after the demise of the original Great Western Arms Co., EMF still retains Great Western as a registered brand name. In a karmic gesture, EMF announced a new “Great Western II” single-action revolver line at the 2004 SHOT Show. The Great Western II is made in Italy by Pietta, and it continues that company’s reputation for outstanding quality and value.

It’s ironic: For 50 years, some people mistakenly said Great Westerns were made in Europe. Now they’re right!

EMF estimated that 50,000 total Great Western revolvers were made, including kit guns. That’s not a bad record, considering the company only manufactured guns for about eight years. That also means Great Westerns are scarce enough to excite collector interest.

Referring to the obsolete .225 Winchester cartridge, Frank C. Barnes once wrote in Cartridges of the World, “It might be well to hang on to your (.225 rifle) because not a great many were sold, and eventually some gun writer will rediscover it as the greatest .22 varmint cartridge conceived by the mind of man, and at that point all your shooting friends will wish they had one, too.”

A similar situation exists with Great Western revolvers. Once considered the pariah of single-actions, they’re now quite collectible.

That derives partly from Great Western’s status as the first Colt clone, partly from the relative scarcity of their guns, and partly from the high quality of most later examples. The bane of any small manufacturer is inconsistency, however, and the quality of existing Great Westerns is across the map.

My Great Western Frontier .38 Special is a good example. Bearing serial No. 17882, it is midproduction gun, probably from 1957 or 1958. Almost 50 years old and showing signs of heavy use, it is still tighter than many brand-new Colt clones. The click-click-click-click of its action is still crisp and positive. Fore- and-aft cylinder play is almost nonexistent, and its indexing is flawless. So what’s to criticize?

Its finish, that’s what. Although the gun has obviously been ridden hard and put away wet, enough of the original finish remains to make a judgment call. It actually has fingerprints in the cyanide-dip case-hardening on the frame, something I would not have thought possible. I don’t mean faint fingerprints, either. I mean permanent, indelible fingerprints sharp enough to scan into an FBI database.

The back of the hammer shows obvious tool marks. The cylinder base pin latch has burrs on it. Even looking past the holster wear, it’s obvious the revolver is not a jewel in the crown of Great Western. This has no effect on the gun’s shooting qualities — it’s as accurate as any single-action I’ve fired — but it makes me wish the company had spent a bit more time on fit and finish.